Language and learning are inextricably linked because the latter is hard to achieve without knowledge of the former. Language consists of words used in a structural and conventional way which is the principal method or system of communication communities use to engage with each other and the world (Britannica, 2026; Winch et al., 2020, p. 12). Language can be spoken, written or gestural and its effective use is a fundamental principle underlying a person’s ability to actively engage with their society. Therefore, by this definition and in conjunction with the cognitive model of reading, learning, and literacy by extension, can only occur if a person is competent in using language in its different fields, tenors and modes (Winch et al., 2020, p. 13). The role of the teacher librarian and the library in literacy development is to support language, literacy and learning across the curriculum through the broadening and deepening of student vocabulary by improving semantic understanding of key vocabulary and building background knowledge with quality resources.

Winch et al., (2020) point out that language is an identifiable way for cultures to share meaning with each other and to achieve a common purpose and as such is influenced by context. One subset of language influenced in this way is vocabulary because it is the knowledge of words that exist in a particular language or subject and or the total volume of words known by a particular person (Cambridge, 2026). Therefore it can be inferred that a person’s breadth and depth of vocabulary knowledge is based upon their experience and exposure to a variety of texts (Winch et al., 2020; Lewis & Strong, 2021, p5). A person that reads or is exposed to a wide range of vocabulary through various genres will be highly receptive to new terminology. However, that does not translate into an expressive capacity unless they are able to practice it sufficiently.

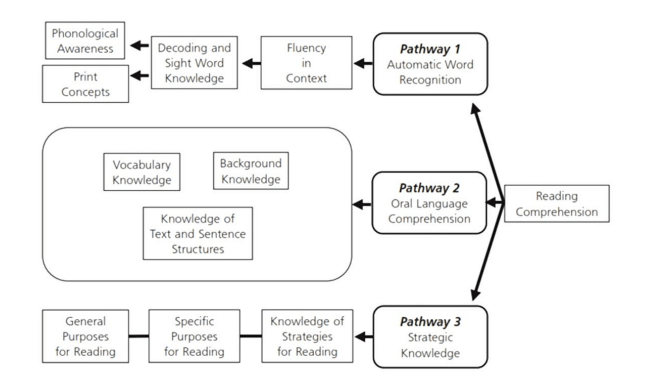

Vocabulary can also be perceived to be a bridge between the written and spoken modalities because readers need to be efficacious in their ability to predict and build mental images from the text (Winch et al., 2020, p. 20). This perception is consistent with the constructivist approach to reading because text comprehension is the result of a reader’s ability to combine what is known, with what is presented in the text in order to arrive at new knowledge and understanding (Graves et al., 2019; Winch et al., 2020, p.91; Spence & Mitra, 2023). Competent readers have the additional advantage when it comes to informational texts because they are able to determine the genre and purpose of a text by making predictions based on their knowledge of text structure and the language or vocabulary within the text.

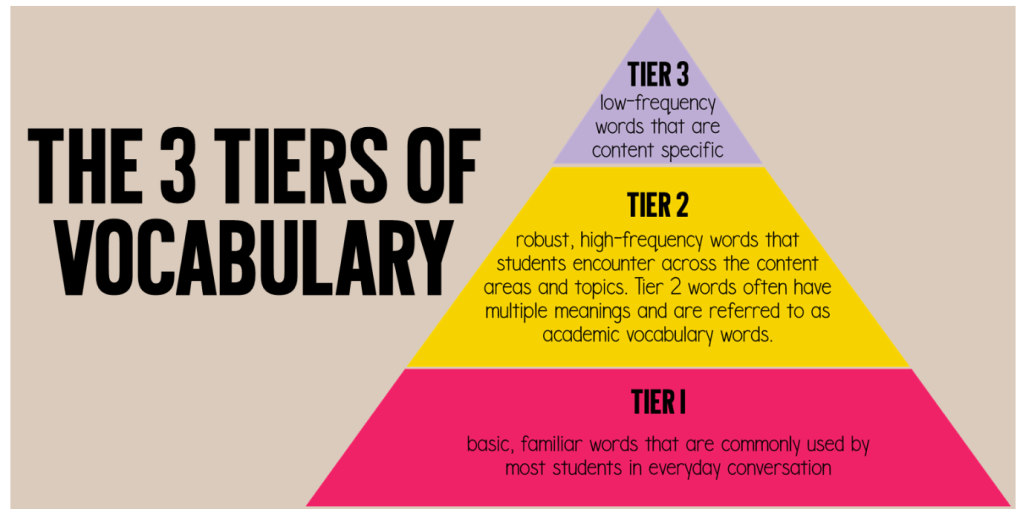

The cognitive model of reading is centred on a reader’s ability to comprehend language because vocabulary acts like a conduit between the working and long term memory impacting ability to effectively comprehend a text (Graves et al., 2019; McKenna & Stahl, 2009; Winch et al., 2020, p82; Spence & Mitra, 2023). A person with a high vocabulary is more likely to have increased success in reading comprehension because their capacity to understand and connect to the text is greater than someone with a limited vocabulary (Winch et al., 2020, p21). This in turn fuels their ability and capacity to read more, further increasing their capacity. This efficacy, as Lewis & Strong (2021) point out, confirms the commonly known Matthews effect as students learn 15% of new words in contextual reading and that they need greater than twelve encounters with a particular term or phrase to even think of including it into their knowledge schemas. However, even confident readers may be confronted when exposed to factual or informative texts because of the leap in cognition required as each discipline will have their own structure, grammar and specialised vocabulary (Spence & Mitra, 2023). This means both experienced and inexperienced readers will require explicit instruction in semantic knowledge to effectively decode and encode text of increasing complexity (Winch et al., 2020, p.110; Lewis & Strong, 2021, p.7).

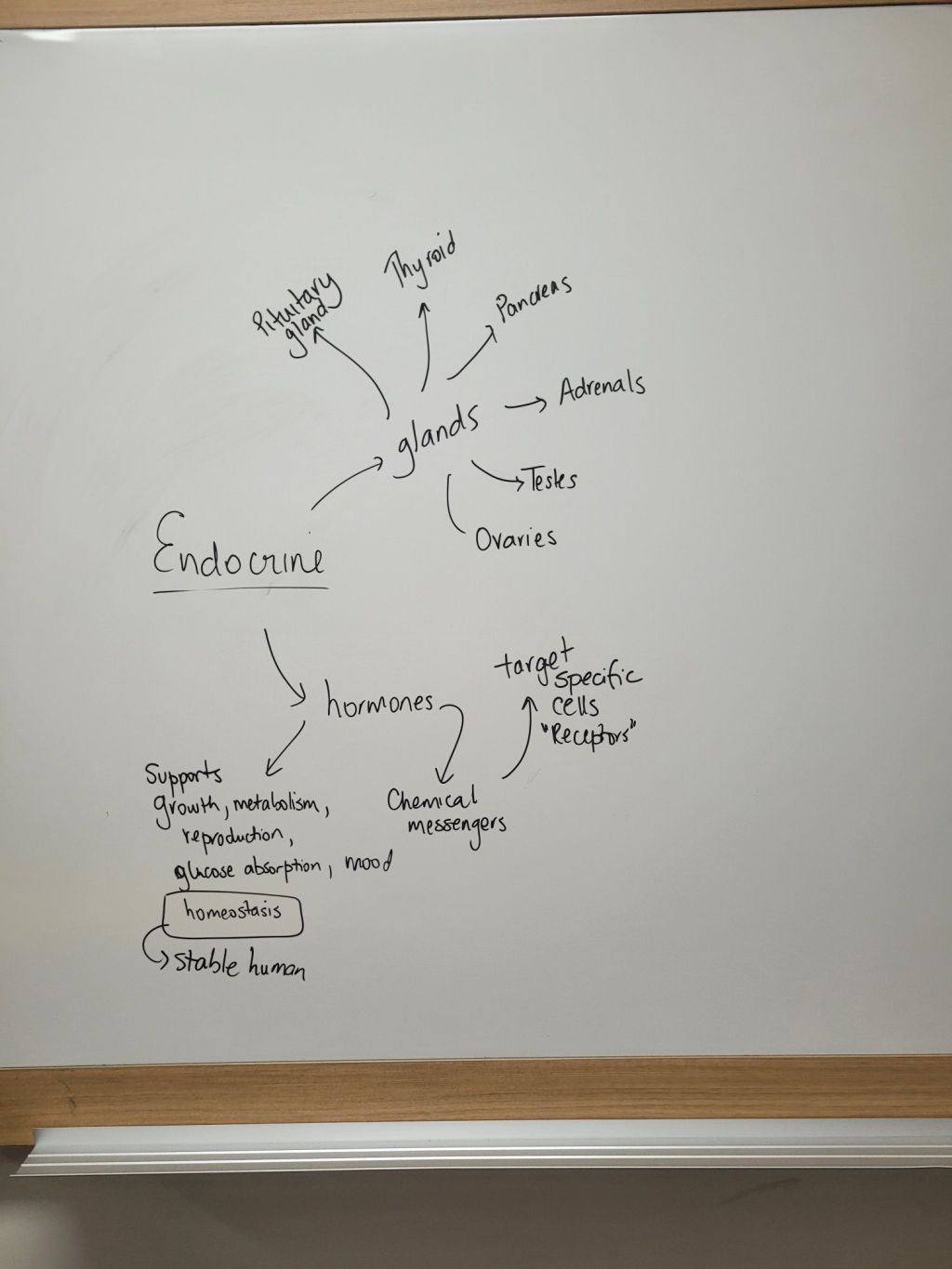

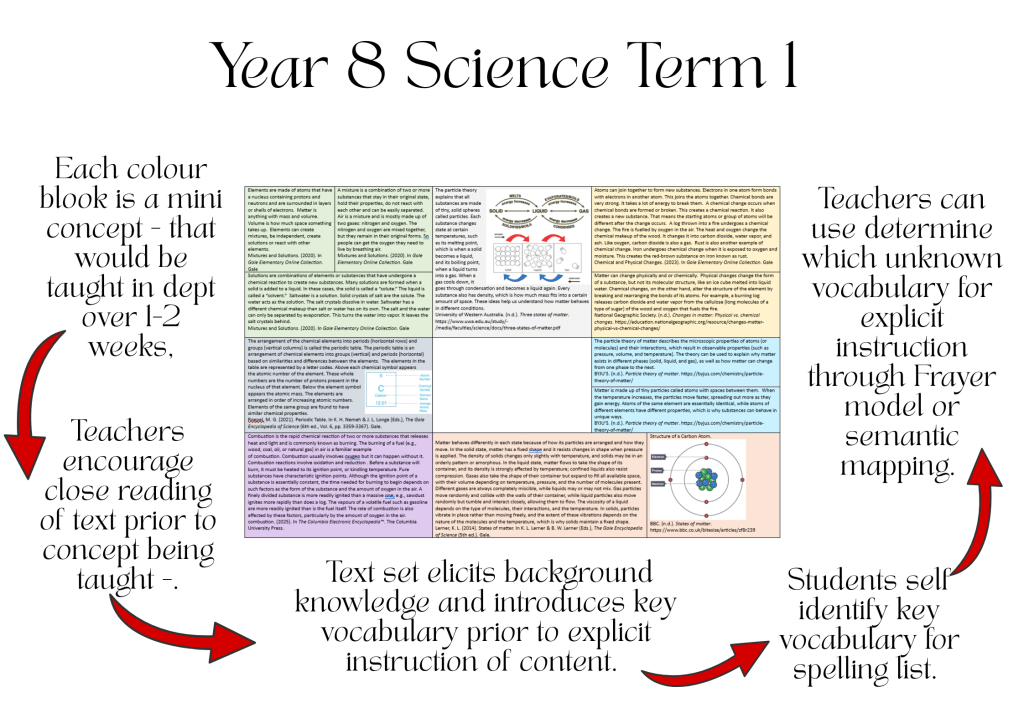

Reading comprehension skills can be supported across the curriculum by increasing a student’s semantic knowledge and background understanding of a topic prior to close reading (Lewis & Strong, 2021). Several pedagogical practices including semantic mapping of tier three vocabulary, the use of text sets to bolster background knowledge as well as explicit modelling of reading strategies can be used effectively to improve reading comprehension and build student capacity (Lewis & Strong, 2021; Spence & Mitra, 2023) However, caution must be used when deciding what text to use in teaching and learning because the use of text can be a limiting factor if infantile resources are used as it limits student capability and capacity (Winch et al., 2020, p114, Lewis & Strong, 2021, pg. 10). Spence & Mitra (2023) point out that it is preferable to scaffold students to complex texts than to provide resources that are age and stage inappropriate.

Text sets are an effective pedagogical strategy to improve vocabulary in a classroom because they encourage students to interact with a wide range of quality, genre specific texts throughout a unit of work. These text sets were specifically curated to improve vocabulary and by extension, reading comprehension. Students were able to engage with short extracts of text that have been appropriately levelled prior to the unit commencing and then were able to re-engage with this text intermittently through the term. This ‘dipping’ in and out of the content allowed students to activate their prior knowledge as well as exposed them to tier two and three terminologies at smaller and more regular intervals. This intermittent exposure is ideal for spaced retrieval practice as teachers are able to regularly gauge the level of background knowledge and understanding the students already have on the topic and as well check for understanding. Furthermore, these vocabulary text sets can be effectively used as text exemplars because they can be formatted to meet the disciplinary genre requirements.

The teacher librarian and library play pivotal roles in supporting language, literacy and learning across the curriculum. Firstly, teacher librarians are well placed to source texts that build semantic and background knowledge. They are able to create and curate text sets, lib-guides, reading lists and book boxes that meet the language and literacy needs of the students. Text sets can be very effectively used to build background knowledge and can be used across classrooms, cohorts and units of work. They can be paper or digitally based; extracts of texts or whole articles; picture books, novels or biographies. They can also be used to explicitly teach vocabulary in discipline specific genres. Teacher librarians can also use their central role in the school to replicate reading strategies across the curriculum, sharing similarly structured resources through various faculties or disciples for a more concerted and systemic approach to literacy and learning. Lastly, teacher librarians are the curators of their collection, and their role is essential to ensure that high quality literature and resources continue to be available to staff and students.

References

Cambridge University Press. (n.d.). Vocabulary. In Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved February 23, 2026, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/vocabulary

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2026, February 6). Language. https://www.britannica.com/topic/language

Graves, M. F., Elmore, J., & Fitzgerald, J. (2019). The vocabulary of core reading programs. The Elementary School Journal, 119(3), 386–416. https://doi.org/10.1086/701653

Hiebert, E. H. (2020). The core vocabulary: The foundation of proficient comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 73(6), 757–768.

Lewis, W. E., & Strong, J. Z. (2021). Literacy instruction with disciplinary texts: Strategies for grades 6–12. Guilford Publications. New York

McKenna, M. C., & Stahl, S. A. (2009). Assessment for reading instruction (2nd ed.). Guildford Press

Mitra, A., & Spence, L. (2023). Educational neuroscience for literacy teachers: Research‑backed methods and practices for effective reading instruction. Routledge. New York.

Winch, G., et al. (2020). Literacy: Reading, writing and children’s literature. Oxford University Press. Docklands, Australia.