Women, Memory and Exile: A School Library Reflection

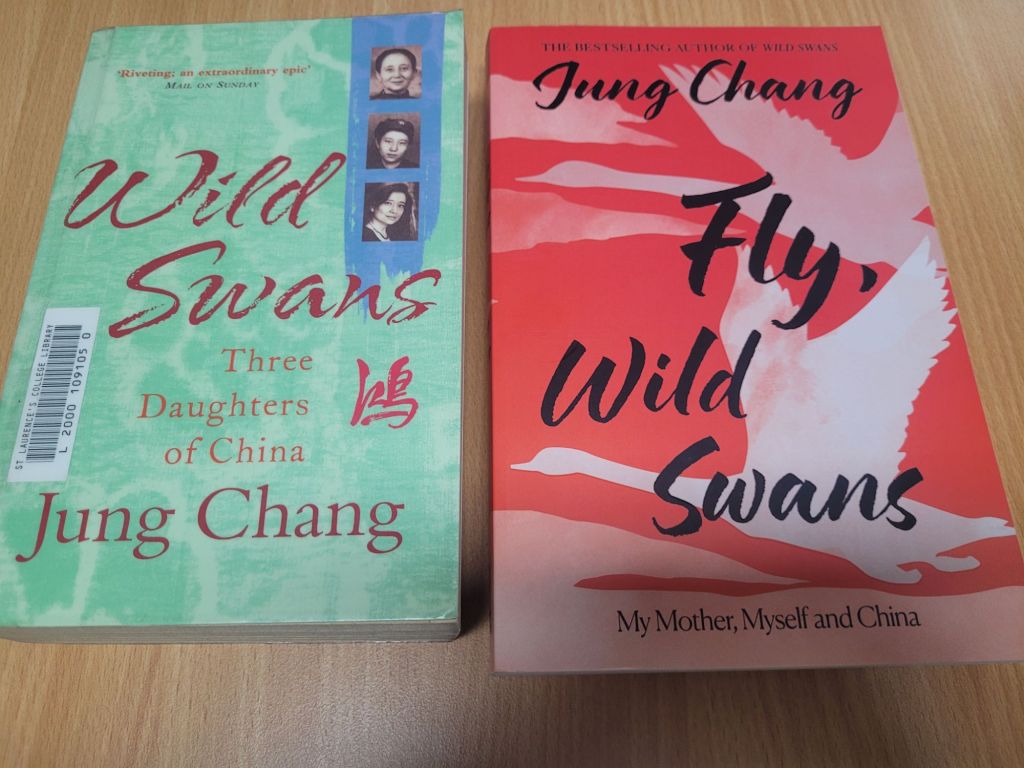

Adding Fly Wild Swans to our school library felt like a natural continuation of a legacy. Wild Swans has long stood as a canonical piece of literature, a book that captures the struggles of three generations of women against the backdrop of China’s political upheavals. In her second publication Fly Wild Swans, Jung Chang turns her gaze inward, reflecting on the cost of telling that story and the way truth can estrange a writer from her homeland. It is a pensive work that reminds us how women across centuries have shouldered familial and societal expectations, carrying memory and resilience even when nations would rather forget.

For students, these books are more than history. They are lessons in courage, in the power of memory and in the resilience of women who endured both familial duty and political oppression. Wild Swans explores the tension between tradition and rapid government‑driven progress. What was presented as modernisation often meant the destruction of customs and the breaking of family bonds as the Cultural Revolution tore families apart and demanded loyalty at the expense of tradition. Her story gave voice to three generations of women living through the upheavals of Mao’s China and this new work is written not only of her mother and her homeland, but of the burden of truth itself, and the cost of bearing witness when a nation would rather forget.

Fly Wild Swans reveals the aftermath of telling that truth, showing how a writer can be celebrated abroad yet silenced at home. Jung Chang turns her gaze inward, reflecting on the cost of telling that story and the way truth can estrange a writer from her homeland. Unlike Wild Swans, which focused on her mother and grandmother, this new work is more personal. It explores how writing Wild Swans changed her life, both opening doors in the West and closing them in China. There is a deep melancholy in her reflections on being unable to freely return to her birthplace. The success of Wild Swans brought her recognition abroad but estrangement at home. This tension between belonging and exclusion mirrors the broader story of women in history, who have often been celebrated for their endurance yet denied the freedom to define themselves.

I chose to buy Fly Wild Swans for my school library because it is a book that students should encounter, not only for its historical insight but also for its profound exploration of resilience, identity and the role of women in shaping and surviving history. Adding Fly Wild Swans to our collection ensures that the conversation continues, allowing readers to see how the legacy of truth‑telling reverberates across generations.

By placing both works on our shelves, we invite students to consider how politics, family and identity intersect, and how women across centuries have borne the burden of expectation while still finding ways to endure. These books remind us that literature is not static. It evolves, it questions and it carries forward the weight of generations.