Reading is widely recognised as a critical skill for young people, supporting the development of strong cognition, mental health and empathy. A growing body of research consistently shows that recreational reading in particular is linked with academic achievement, improved emotional regulation and more nuanced interpersonal understanding. Building a culture of reading, therefore, is not a peripheral task for schools. It lies at the heart of nurturing thoughtful, resilient and socially capable young people.

Yet despite these well established benefits, many children and teenagers do not naturally turn to teachers or teacher librarians for book recommendations (Merga, 2012). To be blunt, young people do not necessarily see adults as cool. Recommendations from teachers, no matter how well intentioned, may lack what adolescents consider to be genuine social credibility. The street cred factor is real, and it is powerful.

This dynamic is clearly supported in contemporary research. Rutherford, Singleton, Reddan, Johanson and Dezuanni’s report Discovering a Good Read: Exploring Book Discovery and Reading for Pleasure Among Australian Teens found that teens prefer “recommendations from friends (57%)”, a finding emerging from a nationally representative survey of more than thirteen thousand Australian secondary students. These findings reinforce what many educators observe anecdotally. Reading among teens is not only an individual cognitive task but also a profoundly social practice.

Further evidence comes from the work of Dr Margaret Merga, a well respected Australian researcher in literacy and reading engagement. In a mixed methods program examining the influence of social attitudes on reading behaviours, Merga (2012) noted that “perceived friends’ attitudes can have a more significant influence on boys than girls, [therefore] making books socially acceptable for boys should be a priority for educators.” This underscores the idea that book talk among peers is not merely casual chit chat. It is a mechanism of social permission. When books gain traction within a peer group, they gain legitimacy and ethos (Merga, 2012; Merga 2014).

Australia Reads similarly emphasises the importance of social engagement in building sustainable reading habits. Its principles highlight that young people need “positive social reading experiences” and opportunities to “recommend, discuss and share books and other texts in ways that are personally enjoyable and relevant”. In other words, reading thrives when it is relational.

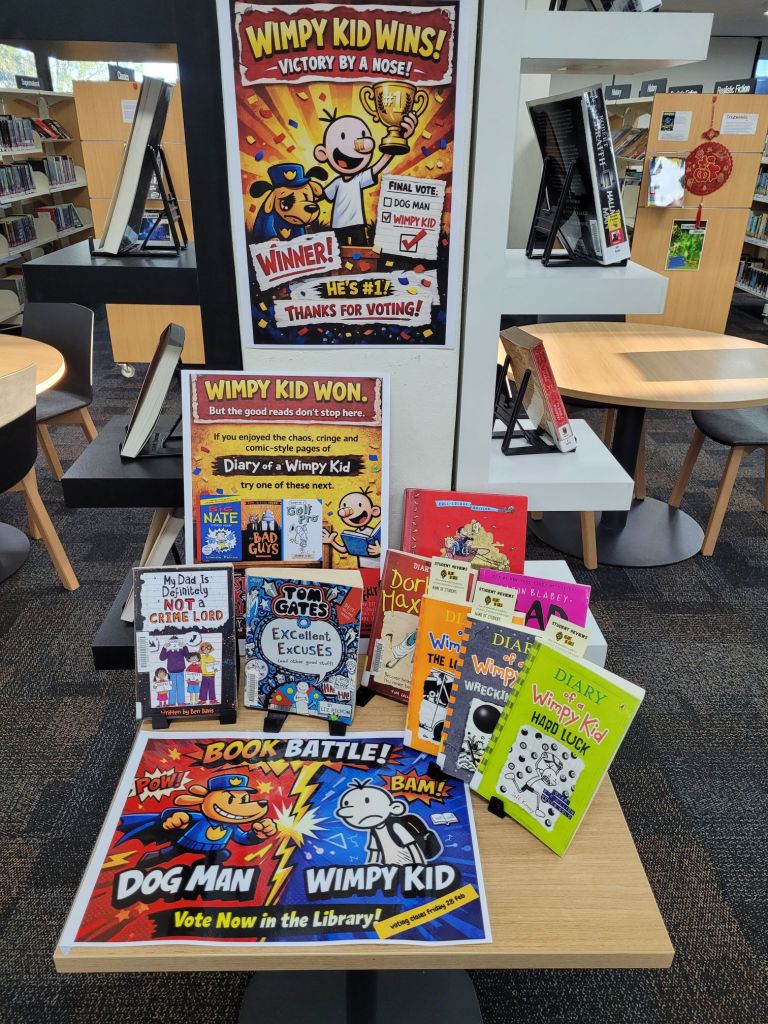

At Lauries, we see these principles in action every day. While staff recommendations certainly have their place, it is peer driven reading culture that most reliably sparks curiosity, especially among reluctant readers. This is why we actively encourage students to reflect on and review the books they read. Their voices matter. Their opinions shape the reading landscape for others. The broader research base supports this emphasis on social recommendation and discussion as a driver of voluntary reading.

A visible expression of this culture is our wall of Lauries Lads Lit Picks. This growing collection showcases books that our students have personally endorsed. We often see reluctant readers wandering over, flicking through the displayed reviews until they discover a familiar name. That moment of recognition is powerful. When a friend or respected peer has enjoyed a book, the barrier to entry drops dramatically. The book becomes not just a text but a shared experience waiting to happen. The pattern aligns with evidence that peer attitudes and friend recommendations play an outsized role in adolescent book choice.

Cultivating a socially rich reading environment therefore requires more than simply providing access to books. It involves elevating student voice, valuing peer influence and creating spaces where reading is openly shared, discussed and celebrated. The evidence is unequivocal. When young people are given opportunities to recommend books to one another, their engagement deepens and their confidence as readers grows. Reading becomes woven not only into their academic lives but into their friendships, identities and everyday conversations.

By continuing to champion peer driven discovery, we support our students not only to read more but to read with curiosity, connection and purpose. That is a foundation that benefits them far beyond the walls of the library

references

Australia Reads. (2025, September 23). Major new report offers 6 key principles to support young people’s recreational reading. https://australiareads.org.au/news/6-principles-support-young-people-reading/ [australiar…ads.org.au]

Crowther Centre. (n.d.). Getting young people to read. https://www.crowthercentre.org.au/resources/getting-young-people-to-read/ [crowtherce…tre.org.au]

Merga, M. K. (2014). Peer group and friend influences on the social acceptability of adolescent book reading. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57(6), 472–482. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.273 [researchgate.net], [periodicos…pes.gov.br]

Merga, M. K. (2012). Social influences on West Australian adolescents’ recreational book reading [Conference presentation]. ECU Research Week. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/41527861.pdf [core.ac.uk]

Rutherford, L., Singleton, A., Reddan, B., Johanson, K., & Dezuanni, M. (2024). Discovering a Good Read: Exploring Book Discovery and Reading for Pleasure Among Australian Teens. Deakin University. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/247629/ [eprints.qut.edu.au]