Lunchtime in a library can sometimes be overlooked as a quiet or transitional part of the day. In reality, it is one of the most powerful opportunities libraries have to connect with their community. Lunchtime events turn a regular break into a moment of discovery, drawing people into the space, engaging those who may feel unsure or disconnected, and strengthening the library’s role as a welcoming and active hub.

Library events are vital for building a rapport between a school community and their library because participating in a simple activity can lead to conversations. From there, it becomes easier to talk about books, recommend reading, or explain what the library can offer. This is because for many people, a lunchtime event is someone’s first positive and relaxed experience in the library, helping them feel more confident and welcome. The brilliance lies in the fact that lunchtime events naturally attract foot traffic. Students and staff are already moving around, looking for somewhere to go or something to do. Hosting activities during this time removes barriers to participation. There is no need to stay after hours or commit to a long session. People can simply wander in, take part, and head off again because these activities are flexible and easy to join. Not everyone wants a formal workshop or a structured program during their break. Drop in challenges and creative prompts allow people to engage at their own pace, whether they stay for two minutes or twenty.

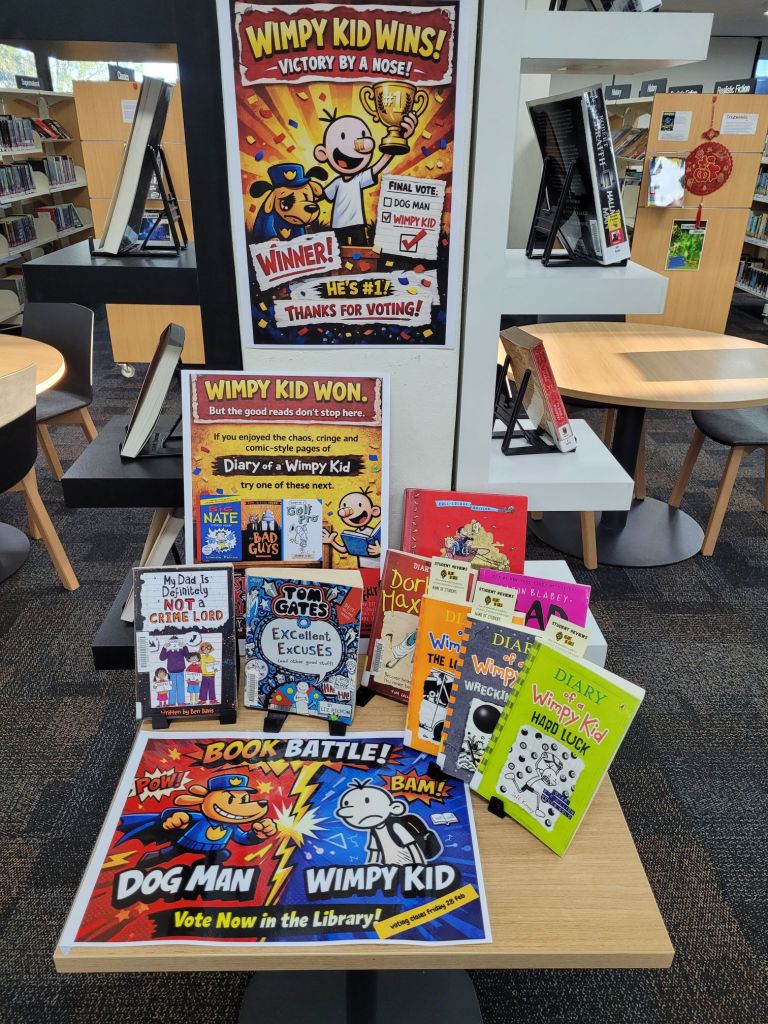

Furthermore, connecting lunchtime challenges to theme days and seasonal events helps keep them fresh and relevant. It gives people a reason to take part right now and adds a sense of fun and anticipation. Over the past few weeks, our library has run challenges such as Heartfelt Haiku for Valentine’s Day and Library Lovers’ Day invited participants to reflect on their love of reading and libraries. Lantern making for Lunar New Year created a hands on way to celebrate culture and tradition. A recent voting challenge between Dog Man and Diary of a Wimpy Kid tapped into popular reading interests and friendly competition. Now, in this past week, the Falling into a Book challenge has encouraged readers to embrace the new season with a new story.

Lunchtime events transform the library into a social and welcoming space. A table set up with a challenge, a craft activity, or a voting station often sparks curiosity. Someone who had no intention of visiting the library may step inside just to see what is happening. Once they do, they are surrounded by books, displays, and friendly faces. Lunchtime events create opportunities for spontaneous engagement that might not happen at any other time of day. They also show that the library values participation in many different forms, not just quiet reading. Afterall, when people participate together, even briefly, they share experiences that build a sense of belonging. Over time, these shared moments help strengthen relationships between library users and staff. The library becomes known not just as a place to borrow books, but as a place where people feel comfortable, included, and valued.

Lunchtime events quietly demonstrate the broader role of libraries. They show that libraries are dynamic spaces that respond to their communities, encourage creativity, and support wellbeing as well as learning. School libraries that use their lunchtime activities or challenges to build connections and rapport with their communities can turn an ordinary break into a meaningful connection and remind everyone why libraries matter.